So, I sold a story to Interzone a few weeks back and didn’t blog it / tweet it as I was struggling with the Fantastic Stories launch, which was a bit delayed by, well, totally predictable web stuff.

So, I sold a story to Interzone a few weeks back and didn’t blog it / tweet it as I was struggling with the Fantastic Stories launch, which was a bit delayed by, well, totally predictable web stuff.

The story, titled A Minute and a Half, is one of the half dozen pieces started and abandoned after my Clarion; it’s packed with ideas, with a world which is now a combination of the future and the future as seen from the past, and of course, it’s full of my own personal brand of tortured four-dimensional autobiography.

This was the last story ‘finished’ before I threw in the towel, and ended my First Try.

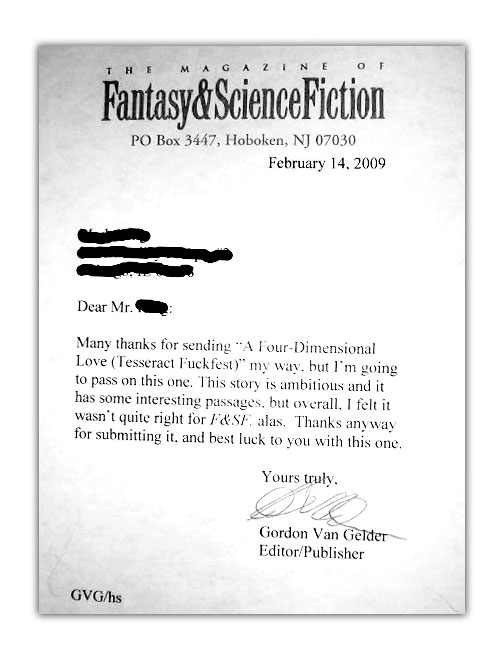

I obsessed a lot about the stories in the mail, at Asimovs, Analog, F&SF, SF Age… the semi-pro presses I was affiliated with were going bust; my third, SFWA qualifying sale to Aboriginal SF vanished with the magazine, and I was emmeshed in tech bubble culture; playing with various kinds of design and production tasks, websites and CD-Roms and industrial videos and writing testing and training materials for, well, money. I was making a lot of money for the first time in my life.

By the time my last SF story limped back to me in my own SASE (look it up, kiddos) , I was done. I wrote, like a little pissy prima donna loser whiny cry-baby, ‘the last straw’ on a form reject from Asimov’s, put the reject in my rejection folder, and filed it away.

Fuck three cents a word magazine fiction, I thought. I’m going to be rich man.

So that didn’t work out…

…which is good, right? Because, hey, I’m writing again! And no, I am not sure whether that statement was ironic or not.

I really loved this story, though, which was titled Cafe Angst at the time, and I wrestled with it over the years, along with a few others, all of which have now been sold and or published, to Asimov’s or F&SF.

Cafe Angst was a virtual cyberspace version of the old USENET group, alt.angst, a dismal place, exactly what you probably would think it would be from the name, where an old, dear ex-friend of mine used to hang out, Dawn Albright. (I remember hopping off the plane from Clarion and attended her wedding to another ex-friend of mine, Peter Breton. I’d introduced them…)

Anyway.

I had a friend in the 90s, Glenn Grant, who I had known mainly through my friend Ron Hale Evans, who had sold a trio of stories to Interzone, which I’d read and loved. Coincidentally, I bumped into him at Readercon 2014, and he was unbelievably welcoming and supportive, funny, smart and kind.

So Glenn, I got in!

Sheila Williams at Asimov’s gave me some insight as to what was wrong with the story, but didn’t ask to see a rewrite. I took her suggestion and surgically removed about a third of the thing. What was left, after another rewrite, seemed clear, it made more sense, it was more emotionally cohesive and the excised third, to be honest, had become a room full of used furniture over the intervening years.

I lost a character I loved in the process, though, a woman named Cosine, who was based on a woman from my Clarion 94 class, Syne Mitchell, one of the many people in my class who went on to publish novels after the workshop.

Cosine went, along with Dawn’s Cafe Angst itself (meaning I needed a new title) as I excised a layer of my own personal, ah, stuff, from the story, removing a big stinking slug of metaphorical subtext. Like pus drained from an infected boil.

So this is the thing, right, about my stories? It’s science fiction and fantasy mixed up with life stuff and the endless echoing interior dialog which has been hammering away inside my skull since I was a tiny kid. The voices that don’t ever stop. The love, the friendship, the fear, the regret, the mistakes, the endless romantic daydream, and the occasional shimmering moment of redemption.

It’s real to me. It’s important somehow. So I do it.

Anyway, I hope to hell people like this goddamn story. Seriously. It was a bitch to get right.