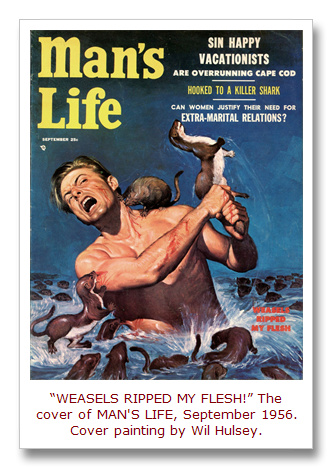

I got this image from Meg Rosoff’s blog, after finishing her delightful and horrific book The Way I LIve now.

It made me laugh very very hard. This gif, not the book. The book made me read it in one day, cry at the end, and go and read about the author. I’m glad she’s not dead. She wrote this book when she was 50, after a life tragedy, and, well, this made me strangely hopeful. Not the tragedy of course. But the writing of a wonderful YA book by a person a half century old who had just suffered a terrible loss.

Because, you know. I’m a half century old.

But now that funny gif is kind of disturbing me. I’m going to put in some spacers to get it to scroll off the page. Follow me down, will you? (I think this post gets positive towards the end.)

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

So, here is the thing

I have never spent my time wisely.

Here is the thing.

I don’t like to think about death, or dying, or things really changing.

And so I don’t spend time as much as I pass it; let it flow. I savor it, pretend it is infinite. I waste it. I revel in it.

I blink in astonishment at my two six foot tall babies. Time. Flowing.

But I don’t plan Time out, or ration it or make any kind of grown up decisions about Doing This vs Doing That.

If I’m honest, though, about my life, about how old I am, 50, and about what I want to try to do, accomplish, say, I have to realize that, I’m out of time to waste. Time is not on my side.

I’m lucky to think I have time, still, to do something, to make some kind of mark. Throughout most of human history, I’d be wrapping it up about now.

One year when I had a job job, typesetting the saddest little four page newsletters you ever laid your eyes on for a business version of a vanity press, I put this big dry-erase ‘year at a glance’ calendar up on a long white wall, and Xed off the days, noting each deadline drop, each piece of ridiculous waste paper designed and delivered.

Staring at the wall, I saw another calendar appear beside it, with the date incrementing, and another, I looked down the long white hall, and I measured the space in my mind and I saw my death out somewhere past the door to the elevator; perhaps in the bar which was strangely just across a small vestibule.

Thank God I was fired.

James Thurber once wrote a book of essays entitled Let Your Mind Alone, in response to the waves of self help books published in the 30s. Yes, we American’s have been trying to Help Ourselves for a long, long time.

In the book, the author is skeptical, of the possibilities of personal transformation, and pleads to be let alone, to be the weird cranky difficult dysfunctional person he is. This has always been my feeling. I identify with my faults as well as my strengths; it’s all me, and really, deep down I love myself in a deeply unfounded, unjustified kind of way I don’t begin to deserve.

If I could hack out all the gooey rotten stuff in me, all the rotten bits, all the dark stuff clogging up my mental plumbing, would the resultant creature even be recognizably me any more?

This is the kind of thing I think about.

In psychiatry this is called maladaptive adjustment. People identifying with their crappy mental states, their crappy diseases.

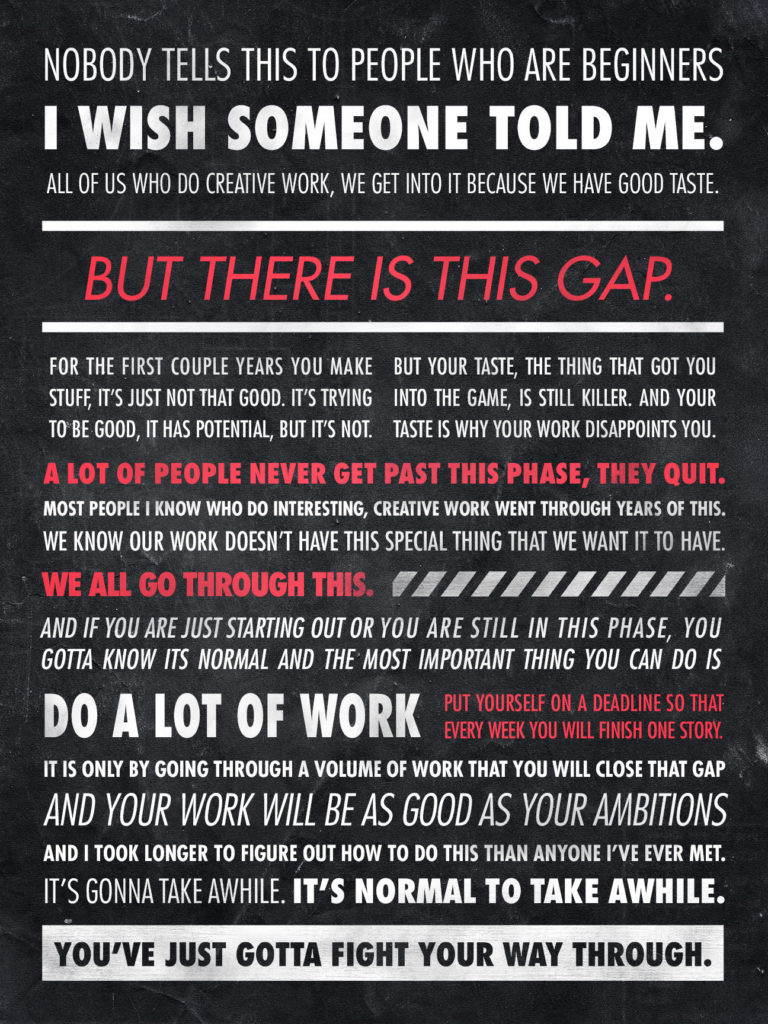

It’s time for me to recognize the fact that my creative output is too low. My process is filled with daydreaming and giving up when things feel bad, and creeping back and starting up again when the bad feelings lose track of where I am. I say I want to write, and then, the world throws freelance work at me and I say, thank God, I really want to be a grown up and make money. I have children for God’s sake.

I want to write a book as good as How I Live Now. That’s what I want to do. I know I probably can’t. (See Black Gooey Bits above.) Knowing that makes it harder of course, much much harder, but I can’t help knowing it. I just do.

So, if I want to accept, that that is how I am, I have to also become a person who does the work anyway, even though at some level I know it’s hopeless. And in that moment, of acknowledging that it’s hopeless, that I’m not very good, that I’m barely coherent, I relax, and just do it for the sheer fuck all of it.

Maybe it’s a blessing.

Maybe it’s good that I know that I suck–maybe that is the only good thing about me.

Maybe this lets me be pure. Be the Zen archer. Makes me not care where the arrow flies. Lets me stop grasping after the writer I’ll never be. The one who writes good metaphors and similes. The one who captures perfect telling details of setting, of character; the one whose dialog sings. The one who has such a wonderful backstory upon which to draw of struggle and challenge and diversity. Insight! Wit! Wisdom!

I want to write books that make teenagers think life will be worth living, that life will be filled with wonderful and awful adventures; that make people know that their hearts will both undoubtably be broken and just as certainly heal.

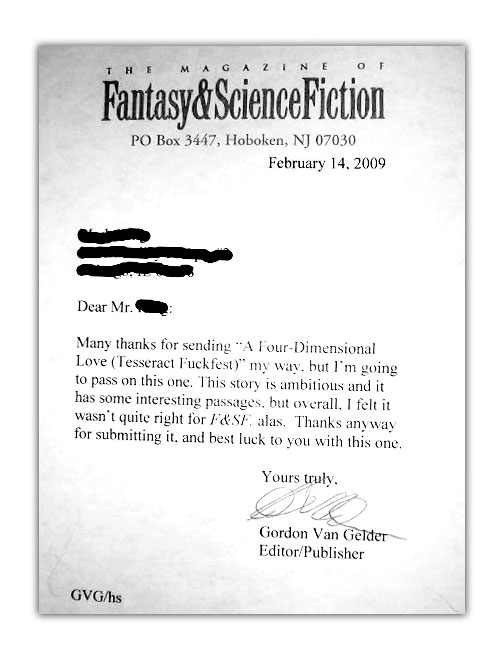

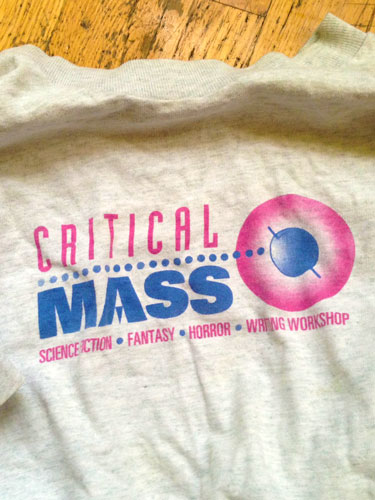

So. Given that, I better get writing. I’m 50. The clock is ticking Time isn’t my friend, but I have the blessing of knowing I am probably doomed, so, I’ll do it for fun, for perversity, for my writing friends… and for Sheilla Williams at Asimovs and Warren Lapine and Ed McFadden and Bruce Bethke and Charlie Ryan and Patrick Swensen and a few others who have published me who I am forgetting, who have somehow failed to get the memo about my worthlessness.

A fact for which I am grateful, when I can muster that emotion.

It’s time for get back in the saddle and embarrass the living crap out of myself.

Onward.

Once Upon a Time, I was going to Be a Writer. Sorry about the capitalization, but there was no avoiding it.

Once Upon a Time, I was going to Be a Writer. Sorry about the capitalization, but there was no avoiding it.